|

Our students are currently heading towards their mock examinations, and usually at this time of year I do an assembly with them to talk about effective revision. But this year we are all on lockdown due to COVID-19, and it seems unlikely that we will be back in school any time soon. So I decided to do something I have meant to do for quite some time: put together a brief guides for students and parents on how to revise effectively. I wanted to build in the elements that I usually present, which are all evidence informed, and present it in a way that would help students identify both why it is important and what they should actually be doing. I have seen other similar ideas before (a couple are linked in the Further Reading section), and there is nothing groundbreaking in what is included. Mine is just another example that people might find useful to share with their students, parents and colleagues.

0 Comments

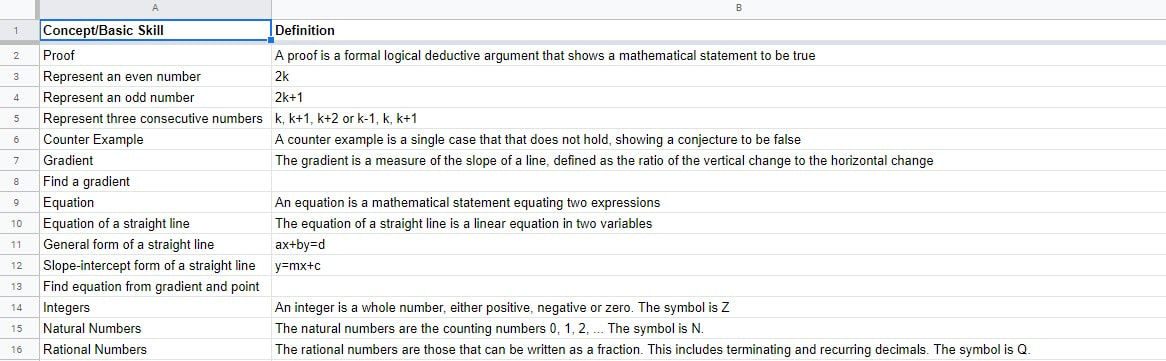

This year I have started trying something new with my IB class to promote their retention of key facts, concepts and skills. I have previously blogged about using the Last Lesson, Last Week, Last Unit, Further Back starters but having had our teaching time reduced I now struggle to feel these are a worthwhile use of time every lesson, and instead have moved to weekly quizzes made up of past exam questions. They get the same number of questions but I mark them and we 'waste' less lesson time in transitions. But I still wanted to do some daily recall (it is a Rosenshine Principle after all!) and with this particular class was a little worried about their knowledge and fluency of key terms and basic skills. I decided to keep a track of the new vocabulary we meet in class, along with key facts and any simple key skills. That is, the things I want them to be fluent in doing. On top of this, I wanted a more systematic way to review these things keeping the spacing effect in mind. To do this I created a spreadsheet! I input the concept/fact/skill into the first sheet and it automatically copies across into the Review Timeline sheet. Then I enter a 1 in the cell that matches when I first taught the concept to students. So in the first lesson of the first week I taught them the concept Gradient and how to find a gradient (The ones before were taught in the taster sessions last year). The sheet then automatically populates the rest of the row with when to do the next review. So the following lesson is a 2 which is the second review. After three more lessons, the 3 tells me when to do the next review. A larger gap appears before the 4th, then 5th, 6th, 7th, 8th and 9th review sessions. We teach the course over six 9 week bimesters, with a final bimester of revision before the exams, so I have set it up for those 6 bimesters. Not all topics are going to get the full 9 reviews, but for gradient the final review occurs in Week 8 of the fifth bimester at which point there is a full 9 weeks between each review. Then for each lesson I look at the lesson we are in (Bimester 1 Week 5 Lesson 2) and look down the column to see which concepts etc I should review. With the current remote teaching I am assigning these as the starting activity as a Google Form for students to do as we wait for everyone to arrive in the Zoom class. I then check their answers and return it using the Google Forms features. My plan is to also increase the difficulty of the skills questions as the review stage increases. When we go back to teaching in a classroom (which seems like it may still be a while off for us here), I am thinking about the best way to do this. It doesn't need to be at the start of the lesson. If you would like to adapt this for your own teaching there is a template version here. There is a template version for having 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 lessons a week. But you might need to adapt the headings for your situation. I suggest only adding extra columns at the end, rather than deleting columns in the middle, as this will mess up the formulas. Obviously, this could be used to schedule a lot more than key concepts etc. Perhaps you could give it to students to help them schedule their revision. Or to schedule when you will set exam questions. Or anything else. But I have found it a very visual way to see the idea of spacing, and it is also useful to help explain what it should look like to students.

There aren't many teachers (or indeed people in general) who would argue with the desire for education to lead to students having flexible, transferable knowledge. That is, that kids learn stuff, but are also able to transfer this knowledge into new an unfamiliar situations easily. As an example from my own subject, we want students to be able to spot when to use Pythagoras' Theorem even when it crops up in a question which has nothing to do with triangles (on the surface), or, even better, when it appears in a different subject (surely the true Holy Grail). All subjects have ideas like this (perhaps this is what we mean by concepts?) that we want students to be able to recognise outside of the narrow confines of the lesson or topic. It is worthwhile spending a few minutes thinking about some of these in your subject.

But as teachers we also know that this is surprisingly difficult to achieve, and are often astounded that students just can't see it when this concept appears somewhere new, especially when we know they can do it.

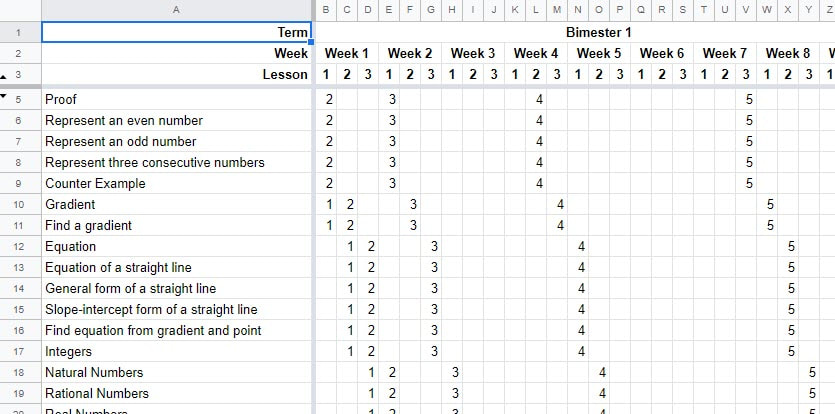

Throughout 2019 I worked alongside two teachers in my department on Checking for Understanding, but early on we diverted to thinking more about what we meant by understanding. Without going into too much detail, we settled on 6 stages of understanding, as shown below in a display I now have in my room.

This made me think about the excellent Daniel Willingham article for the AFT titled "Inflexible Knowledge: The First Step to Expertise", and how Willingham distinguishes between rote, inflexible and flexible knowledge. I would say that our stages 1-4 of our model above are a break down of inflexible knowledge (although 1 could be rote in certain contexts), and that only 5 is true flexible knowledge.

But anyway, the point of this blog was not to delve into the details of the differences between these types of knowledge (read the article above if you want that), but rather to get a bit meta on the idea that inflexible knowledge comes before flexible knowledge can fully develop, which stemmed from this tweet:

If we take the idea that we need to pass through inflexible knowledge to get to flexible knowledge (which is not universally accepted), then this has implications on the understanding of that very statement for teachers.

For teachers to be able to think flexibly about the idea that students need to pass through inflexible knowledge to get to flexible knowledge, the teachers must first pass through an inflexible knowledge of this very idea.

That is, it is completely natural for teachers to know that students need to first develop inflexible knowledge before being able to reach the heights of flexible knowledge, but for those teachers to be unable to apply this to their teaching (which would be showing a flexible knowledge).

If a teacher has passed on to flexible knowledge of the idea that inflexible knowledge is a precursor to flexible knowledge, then they will plan activities to make use of this. Perhaps this would involve using retrieval practice (with higher order questions as suggested here) or something else (this would depend on the individual teachers flexible knowledge of other areas of pedagogy). Once you start to dig a little deeper into this idea, it becomes clear that pretty much everything a teacher does is also subject to this principle. First we learn some new idea, perhaps we play around with it a little, we read more about it, and gradually, as we develop more experience we are able to incorporate it into our teaching practice flexibly.

And that includes our understanding of developing flexible knowledge. This understanding needs to pass through being inflexible before we can flexibly use it.

Thinking about that makes my head hurt, but I think it has implications for teacher professional development. It also make me feel a bit better about knowing I should be doing some things in the classroom, but not being able to do it flexibly.

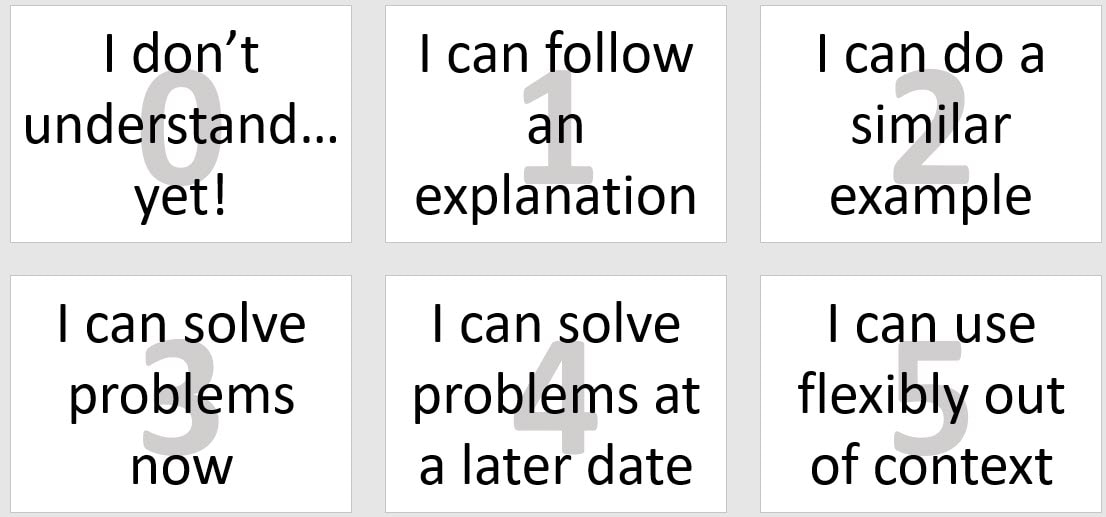

Wholesome Leadership by Tom Rees is a whole approach to school leadership. It is based around the model of the heart, the head, the hands and the health of school leaders, and goes into detail as to what successful leaders in schools do in each of these categories. Throughout the book, Rees tells personal stories of how he has developed as a leader in the different aspects, as well as giving specific examples of his experiences. This personal touch really helps the book feel more authentic, as you can tell it is written by somebody who has lived these experiences. This is balanced nicely by the interviews with others who are (or have been) involved in leadership in education, each giving their own perspective on one of the aspects of the Wholesome Leadership model. Before delving into the nitty gritty, Rees shares a handy planning tool, which he calls the Five Fives, for managing change, a big part of being a school leader. Throughout the book he refers back to this tool, providing a template at the end of each chapter to encourage leaders to engage in planning their changes. Also at the end of each chapter are a series of reflection questions for leaders to use to ascertain what areas they would like to work on in their leadership/school. Combining these with the Five Fives planning tool is an excellent way for leaders to take action after reading the chapter. Illustrated by Oliver Caviglioli, the visuals add to the whole experience of the book. Each chapter starts with a summary of key quotes which gives the reader a nice taster of what is to come. The highlight of the visuals are the WalkThrus for Learning Walks, Appraisal, CAP Meetings and Review Mornings. Each of the four parts of the Heart, Head, Hands and Health model is broken into 3 linked chapters. Although it is an easy book to read all the way through, it is also designed so you can jump to a particular chapter that you are interested in. I can see myself popping back to chapters on a regular basis to reacquaint myself with the ideas, now that I have read the whole thing. I have created a summary document of the book. The image is below, but you can find the PDF version here, which can be printed up to A2 (it also works pretty well in A3). Some more details on each chapter are below that.

I have done a few sessions with students recently on the importance of sleep, as lack of sleep has become a chronic problem for our sixth form students. They are staying awake into the small hours of the morning to complete work that they have left to the last minute, thinking that sleep is a luxury that they can do without. But that is simply not true. Based on my reading of Why We Sleep by Matthew Walker, I have been being more explicit about the dangers of a lack of sleep, but also the benefits of getting enough sleep. I have been particularly focusing on the way sleep relates to learning, but have also been talking briefly about the other health concerns. I have started with a brief introduction to the importance of sleep for the learning process, and I have cobbled together an analogy that I think sums it up quite well. Our brains act like a sponge, absorbing lots information throughout the day. As they day progresses the sponge gets more and more full. When we sleep, it is like squeezing the sponge into a bucket: the new learning is safely stored into our long term memory (the bucket). Day after day we keep adding more stuff to our bucket. Of course, when we squeeze the sponge some of the water splashes out and misses the bucket, and we lose that water, but most of the water is makes it into the bucket. When we wake up, the sponge has been completely emptied, and is ready to absorb a new set of learning the following day. I have been using this analogy to highlight the two benefits of sleep towards learning: firstly it helps consolidate our learning from the previous day by transferring ideas from our pre-frontal cortex into our long term memories; and secondly, it leaves our brains in a more receptive state to learn the next day. Of course, when we do not get enough sleep, we do not fully squeeze the sponge, so not everything makes it to the bucket, and we do not have as much ability to soak up new knowledge the following day as the sponge has not been fully emptied. Or if our sleep is of low quality (such as when we drink alcohol or take sleeping pills), when we squeeze our sponge it is like having a shaky hand, and much less of the water makes it into the bucket. This analogy works for the deep sleep cycles, and seems to get the point across. But it does not work as well for the importance of the REM cycles. This phase of sleeping is also vitally important to learning, as this is the time when our brain starts to make connections. As many mathematicians know (and I am sure many from other walks of life) when we are stuck solving a problem, one of the best things to do is to go away and come back the next day. Part of this is due to the power of the REM cycles of sleep, where the brain continues to work on the problem, accessing that deep bucket of knowledge you have stored away in the daily sponge cleansing. Having talked about the importance of sleep for learning, I then share some of the startling facts and figures that Walker shares:

Many students bemoan that they just don't have time to sleep as they have too much work to do. I point out to them that if they were getting enough sleep then the work would take far less time as they would not be trying to do whilst cognitively drunk, and that, more importantly, their health is far more important than any piece of work. I finish with some recommendations for sleeping better:

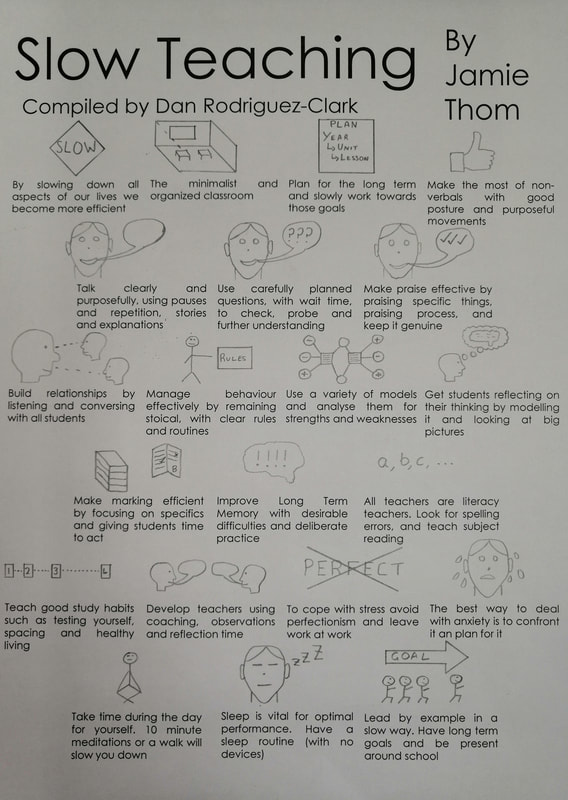

Slow Teaching by Jamie Thom is an excellent book to give you a brief overview of lots of different areas of teaching and learning. The premise of the book is Thom trying to convince us that we should slow down in all the things we do, both in and out of school. And he has me convinced! Tackling topics such as classrooms, relationships, questioning, wellbeing and teacher improvements, each chapter is succinct and to the point. They also all end with a series of Slow Questions, to help the reader reflect on their own practice in light of the slow ideals (given below as an overview of the ideas shared). Thom's main point is that the fast lifestyle of many (mainly new) teachers is unsustainable, and there are many ways to slow down, and actually become a better and more efficient teacher. Taking the slow, thoughtful approach can help us better balance our lives, be better teachers, have better relationships with students, and improve our wellbeing. I have summarised the 21 chapters briefly in this sketchnote. Minimalistic Classroom

Streamlined Planning and Teaching

An Actor's Paradise: The Non-Verbal in the Classroom

Efficient Teacher Talk

Questioning: Rediscover the Potential

To Praise or not to Praise

Refining Relationships

Serene and Stoical Behaviour Management

The Power of Modelling

Developing Motivated and Reflective Learners

Debunking Manic Marking

Memory Mysteries

Literacy: Beyond the Quick Fix Solutions

Teaching the Secrets of Effective Revision

Reflect and Refine: Developing Passionate Teachers

Understanding and Managing Stress

Arming Ourselves against Anxiety

Tacking Teacher Insomnia: Sleep Easy

Embracing Mindfulness: The Meditating and Mindful Teacher

Value-Driven Leadership

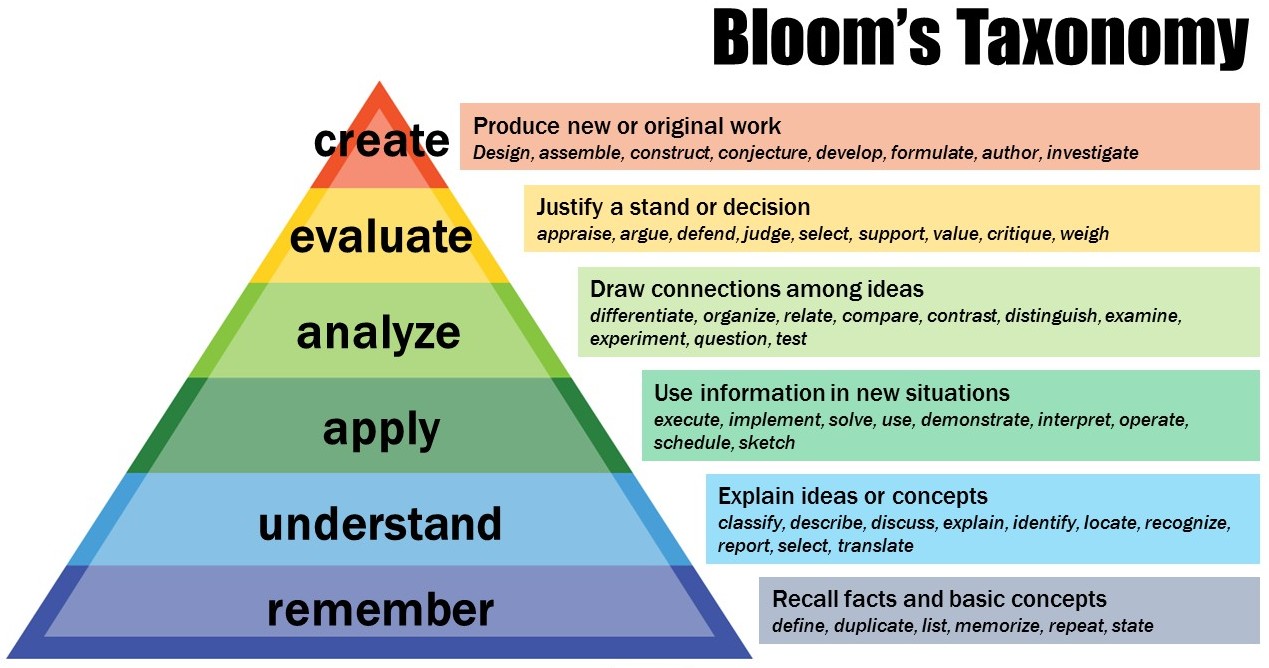

Bloom's Taxonomy and the pyramid shown above are commonly known in educational settings. The hierarchy was designed to help educators push students to higher level thinking, and was intended to help with the development of cognitive abilities. However, I feel that it is often misinterpreted in educational settings. Many people are under the impression that Bloom's Taxonomy says we should always be aiming for the top three tiers of the pyramid. These are the higher order thinking skills we want our students to develop, so these are the ones we should be practising regularly. On the other hand, there are people who see the pyramid and immediately cast it aside, having sat through training sessions stating the above, or just having it hammered at them so often they have grown tired of it. These people argue there is no use in it as it is old (1956) or not based on a thorough research base, which is now significantly more advanced. But I feel both camps are on the wrong track here. As far as I know, Bloom never intended to suggest that we must always aim for the top, and it is this that causes the problems (on both sides). I actually like the Pyramid structure of the taxonomy, as to me it makes things very clear. To achieve understanding, you need a firm foundation of knowledge. To be able to apply your knowledge successfully, you need to understand it. You cannot analyze something if you cannot apply the basic ideas. To evaluate (that is justify your conclusions) you need to first analyse the material. And, finally, to be able to be creative in a domain, you have to be able to justify your opinions first. This is the nature of a hierarchy: they build upon themselves. You have to climb to the top, and it is not possible to jump straight there without doing the ground work. This fits in with my view of creativity as the pinnacle of expertise within a domain. We can only be truly creative when we know a lot about something. As an Art teacher once told me, "You have to know the rules in order to break them" when referring to the work of Pablo Picasso. But there is another aspect of the pyramid image that I like. Notice the size of the pieces. They are not equal. This has two implications:

I want to clarify for the second point I mean throughout school. When students arrive in our class they already have a vast amount of knowledge they have learned (both in and out of school), especially if we teach in secondary education. That means that most of that block may already have been learned, and we can move up more quickly. In general, the further through their studies of a particular subject, the more higher level thinking we should require. However, it is dangerous to assume this is the case. If there is missing knowledge, or even misconceptions, then the other aspects of higher order thinking will be built on a shaky foundation, and, inevitably, will lead to poor performance and less learning. One of our roles as a teacher is to check for understanding and knowledge before moving on to the higher levels of Bloom's Taxonomy. And for those people who sit in the latter of the two camps described at the start? Well, I think this interpretation fits in well with ideas from modern cognitive science. For example, Daniel Willingham talks about How Knowledge Helps, which is saying that the bottom of the hierarchy is really important. I think that there is a lot of benefit to the ideas of Bloom's Taxonomy, but, as with many things in education, when it is misinterpreted it can be killed off. Further Reading on Bloom's Taxonomy

Here are three posts from some of the big hitters in education with their take on the Taxonomy. https://learningspy.co.uk/featured/didaus-taxonomy/ https://theeconomyofmeaning.com/2017/08/24/a-longer-piece-on-the-taxonomy-of-bloom/ http://teachlikeachampion.com/blog/blooms-taxonomy-pyramid-problem/

Over the last year I have grown interested in not only the ideas from empirical studies that we can use in the classroom to improve learning, but also the underlying functioning of the brain and what implications that has for our understanding of how we learn.

In particular I have done two free online courses:

And on top of those I have been reading around the subject. Recently I finished reading the excellent MARGE: A Whole-Brain Learning Approach for Students and Teachers by Arthur Shimamura, which I discovered through this post by Tom Sherrington.

In this post I want to compare and contrast two of the models offered through these experiences: MARGE from Arthur Shimamura and EBC from the FutureLearn course.

First a brief overview of each model.

MARGE

MARGE is the acronym used by Shimamura to stand for Motivate, Attend, Relate, Generate, Evaluate. In the ebook, Shimamura gives both an overview of this model and goes into detail for each of the aspects. He also discusses the brain functions behind each of these.

I recently saw this clip of John Hattie speaking about Inquiry Learning, and why it has such a low effect-size in comparison to some of the other aspects he has looked at in Visible Learning. This is something that has intrigued me since first reading his work, as we clearly want our students to develop into effective inquirers, so why is it that using this approach is not more effective?

I think he perfectly sums up one of the main problems with teaching solely through inquiry, which is that in order to inquire about something, you have to know something to start with. This links to some of the other reading I have done, particularly on the ideas of Critical Thinking and Creativity being domain specific skills, and that in order to develop these skills you need to know a lot about the domain in which you want to apply them.

For example, I am a good critical thinker in mathematics, and am a pretty creative mathematician. I am able to use methods to solve problems that those with less knowledge of maths would not be able to do, even if they knew the methods. But I am a novice photographer (something I am learning at the moment). I am unable (at this stage) to think critically about the lighting of my photos, and be creative with my compositions, when taking photos, even though I know this is what I want to do. It is not through lack of trying, but rather that my knowledge is still relatively low in the domain of photography, and I am having to think about the technicalities of the photography, which would be automatic to an expert photographer.

The same is true of inquiry. I am very capable of inquiring and discovering new mathematical ideas, and I am quite quick at being able to apply these ideas to solving other problems. But in photography, my attempts at new styles are often disappointing until I have some instruction in how to approach them (usually from a Youtube video, or blog post). Even though I have a macro lens, I have never been able to take a macro shot that is a good photo, because I have not invested the time in being properly instructed in how to use it, nor have I then practiced enough at this skill to become better at it, and I will improve very slowly if left to my own devices to play around with the lens.

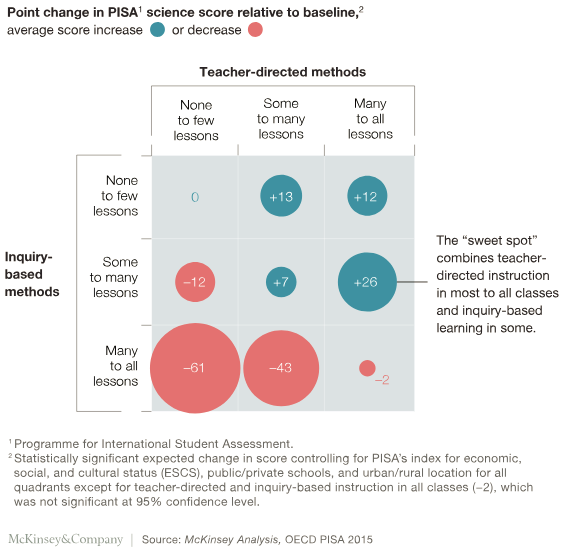

This chimes with the recent findings from the PISA 2015 data that show that the "sweet spot" for teaching is using teacher directed instruction in most to all lessons, and inquiry in some lessons (https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/social-sector/our-insights/how-to-improve-student-educational-outcomes-new-insights-from-data-analytics).

And this brings us back to what Hattie was saying in the clip. No, the low effect size for inquiry learning is not telling us to never do inquiry based learning. It is saying that we should save inquiry for the right time in the learning journey. And this is not at the start, but rather after we have developed a strong foundational base of knowledge and skills. At this stage, inquiry can help us extend and consolidate our learning in an area, but relying too heavily on inquiry in the initial stages of instruction can lead to more problems later on.

Perhaps counter-intuitively, the best way to develop students as enquirers is not to give them lots of practice at inquiry, but rather develop a strong foundational knowledge base, from which they can then base further inquiry.

Perhaps in a few years I will be able to develop new photography skills "on the fly", by trying things out. But for now, I will continue to rely on some instruction from my internet sources!

Suggested Further Reading

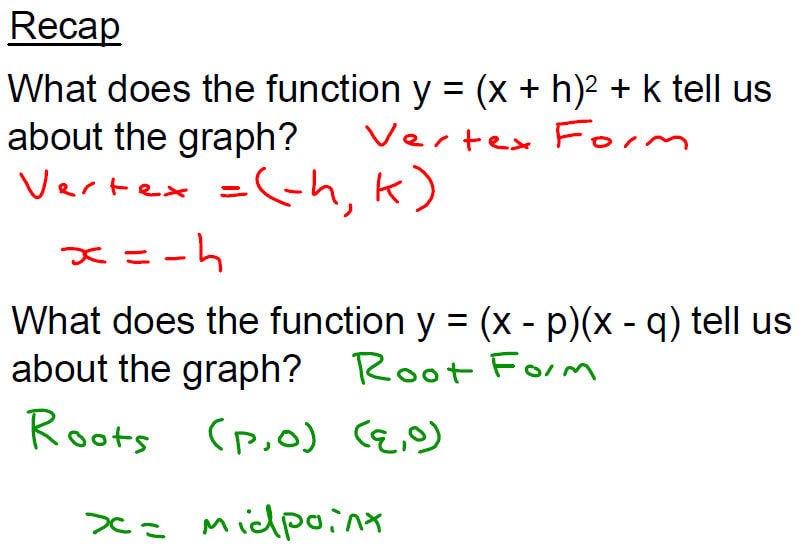

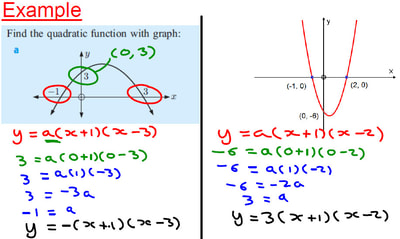

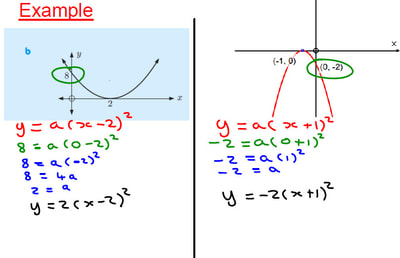

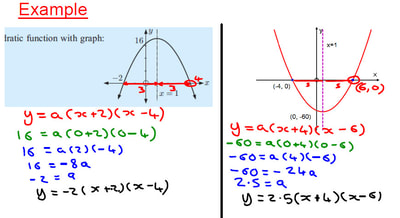

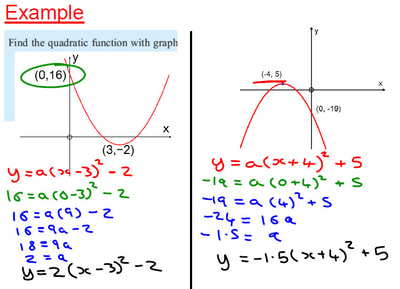

Putting Students on the Path to Learning by Richard Clark, Paul Kirschner and John Sweller. Edu-resources Padlet I have previously shared this padlet of links to blog posts on a host of different areas of Teaching and Learning. Hopefully it will prove useful to some people when trying to find posts from the edu-blogosphere. If you have any suggestions of headings, or blogs for me to include, then please do let me know (might be easiest to do this through twitter). But I have now created a second padlet which focuses on research articles and books. For each article or book that I read I am challenging myself to write a one page summary sheet (one page per chapter for books). This is to act as a quick reminder to me of the key points, but also as a way to help my staff find the time to interact with research a little more (a one page summary is quicker to digest than a 10 page article). For some articles I have also written summary blog posts on our T&L blog, and these are also linked to, along with the original article. I will be adding to this as I read more articles (and updating the ones I read before I started the summaries at some point too). Quadratics from Graphs I have been trying to extend the use of example problem pairs to more of my classes, and have started to use them with my first year IB students. We were looking at finding the equation of a quadratic from a graph, having already covered sketching graphs given in root (factorised) and vertex (completed square) form. We started by recapping the two forms and some of the things they tell us. After this I jumped into a series of example problem pairs of the different type of questions that can be presented. As you can see from the screenshots below, I have been working on my use of colour coding the examples that contain multiple steps. I find this helps me think about the different steps, and also helps the students identify the steps. The examples are taken from our textbook, and the your turns were created using Autograph. I then made use of my Quadratic Graphs Activity that I created a couple of years ago (using Geogebra), to test them on some more examples. I will be making use of this activity again during the coming lessons to induce retrieval and spacing of this complex skill. Revision with S4 I am a firm believer that exam groups need to get lots of practice of past exam questions in the final run up to the exams. Often this will involve doing lots of past papers in class, but to keep it a little bit varied I have done these two activities this week:

Review Homework/Quizzes With my first year IB students I have been having a few issues with some of them doing the homework to an acceptable standard to help them recall. Too many were copying from friends/notes, rather than retrieving. So now I have started to do a quiz based on the homework. They hand in the homework (which is a double sided sheet of approximately 5 exam style questions from topics they have seen previously) at the start of the lesson, and, as before, they do the starter (an past exam question). I will then teach some new content. In the middle of the lesson I give them the quiz (it is a 80 minute double period). This quiz is the same as the homework, but with different numbers. I collect the quiz version, which I mark after class, and they self mark the homework. We are only a couple of weeks into this, but it seems to already have had the desire effect of getting students to pay more attention to their homework, and many students have commented on how they like this to "help them remember" (which I interpret as them liking retrieval). P6 Cover Lesson

I was put on cover for a P6 (11-12 year olds) Maths lesson. The lesson was on the unitary method of proportion, and I was taking the second half of a double lesson, which had already been covered by another Maths teacher in the first period. I walked in to a class struggling to apply the unitary method to an indirect proportion problem (12 workers take 20 hours, how many workers needed for it to take 15 hours). Although they had solved the problem, they were unable to explain why it worked, and my colleague was struggling to see how to apply the unitary method to this particular problem (being a cover lesson, he was caught a little off guard!). This naturally led to a bit of team teaching with my colleague (who has a very different teacher personality to me), with him working on a direct problem on one board and then passing to me to show the indirect problem on another board. The light bulb moment came for most of them when my colleague suddenly shouted "I got it! If it takes 12 workers 20 hours, then there is 240 hours of work! If my 11 friends didn't turn up, then I would have to do 240 hours of work all by myself". The rest of the lesson I just chose questions from the set worksheet, put them on the board and challenged students to work them out in groups. But what I kept doing was linking it back to the words UNITARY, DIRECT and INDIRECT, and making comparisons between the problems as they went up on the board. What's the first thing we have to do? Find the unit! How do we know it is direct? As one goes up, so does the other! How do we know it is indirect? As one goes up the other goes down! What was particularly fun about this lesson was that I "adopted" the personality of my colleague. This took to a way of teaching I haven't done before, and I can certainly see the benefits. Making a big deal out of things really helped it stick in their heads. It comes so naturally to my colleague, but this is certainly something I am going to try to pinpoint what he does, and incorporate it into my teaching a little. |

Dan Rodriguez-Clark

I am a maths teacher looking to share good ideas for use in the classroom, with a current interest in integrating educational research into my practice. Categories

All

Archives

August 2021

|

|

Indices and Activities

|

Sister Sites

|

©2012-2023 Daniel Rodriguez-Clark

All rights reserved |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed