|

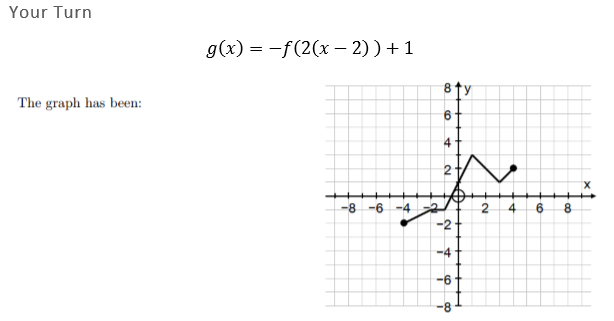

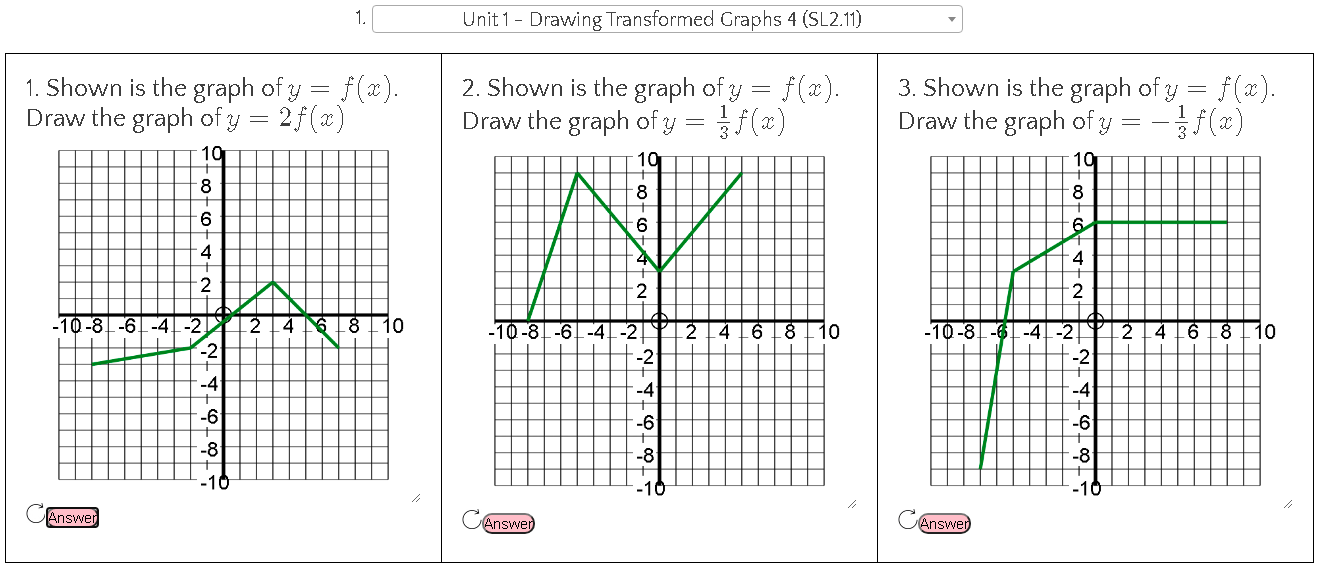

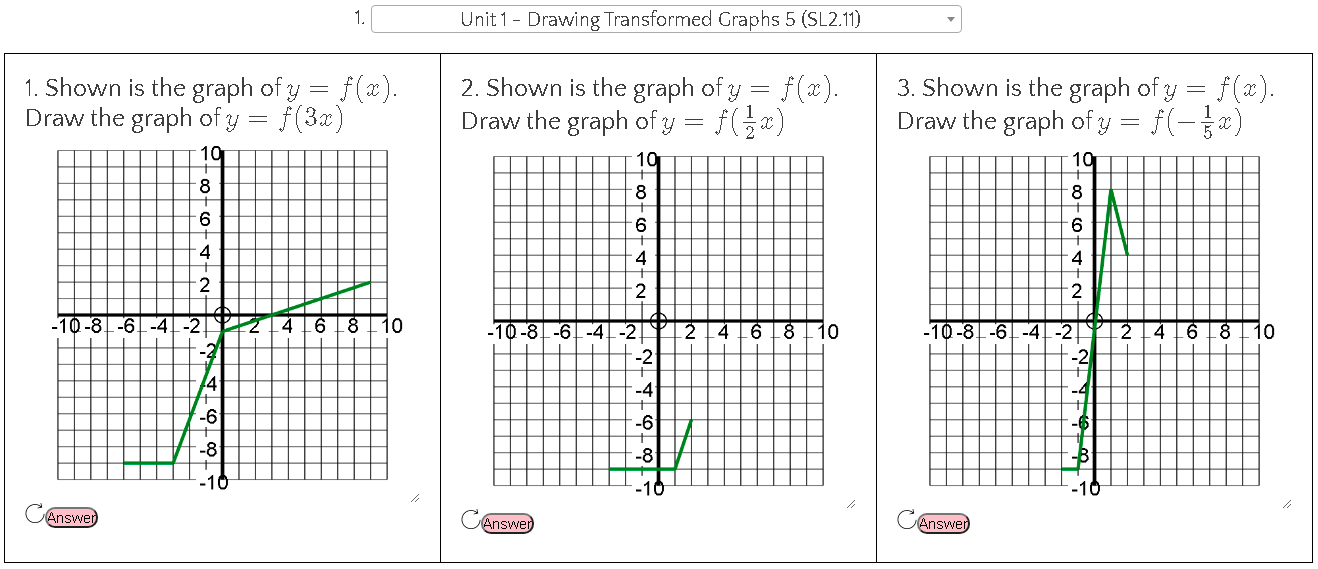

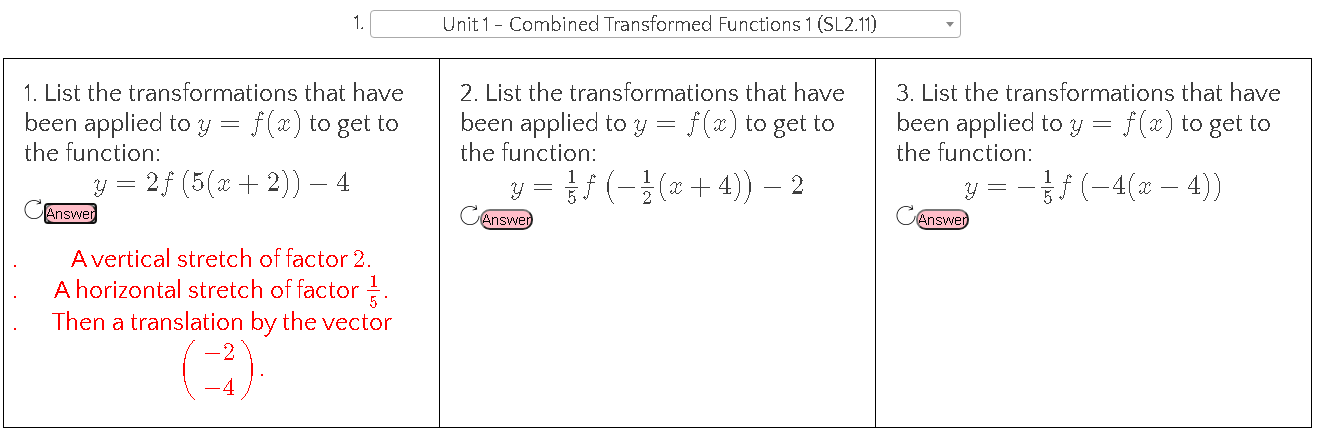

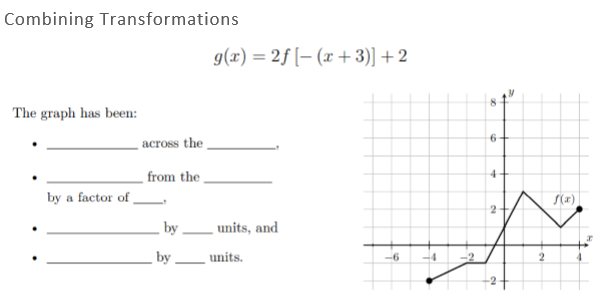

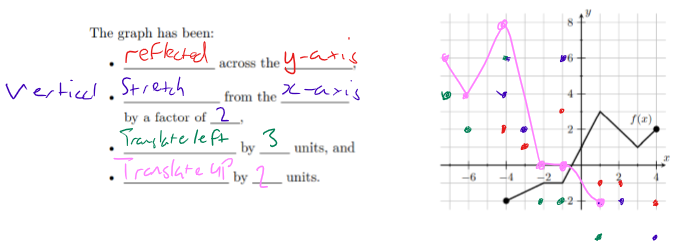

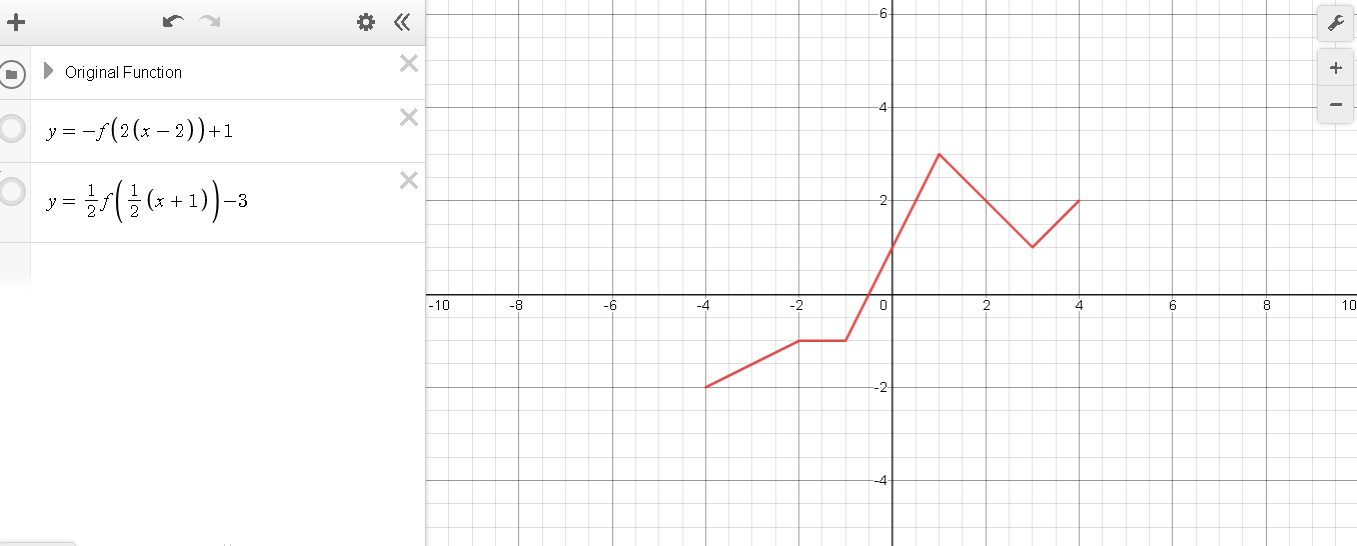

This week I had a breakthrough on how I could teach transforming functions to my IB AA SL students, which as with many of the best ideas, happened almost completely by accident! The lesson was on combining different transformations to draw complicated functions. The end point for the lesson was questions like this where you have a function f(x) and have to draw something like g(x) given below (f(x) was defined earlier in the example, and is shown in the graph). But from the previous lesson I knew that several students were still having issues with vertical and horizontal stretches, especially when the factors are negative, so I wanted to practice these first. I decided to use my IB Key Skills question generator to create 3 questions of increasing difficulty. We started with the ones shown below. This is nothing new. I often do this when I know there are problems for some students. It gives us a chance to discuss as a class the approach to different questions. But what I realised whilst doing this was that I could ask students to annotate on the screen to show their answers. I can't believe it has taken me this long to think of this, but it was equivalent to getting students to the front to draw on the board! Anyway, after kicking myself for not thinking of this earlier, I realised I could do a lot more with it. For starters, I had three students working at a time, and I chose students to work on the level of difficulty that I thought was appropriate for them based on the previous lesson. I asked the other students to work out what their answers would be. When a student had finished their question I asked the rest of the class to use the stamps built in to the Annotate function of Zoom, to either tick, cross or ? each answer. This gave me a feeling of what the class thought (and because I could see the names as they annotated, who was right or wrong). The ? was good too, as it allowed students to show they still weren't sure. For those that disagreed with an answer I asked them to explain why. After we had all three answers done, I pushed the answer button to show the answer. And what worked REALLY well, was when I then scrolled down, the annotations don't move. Usually this is a pain, but in this instance it was perfect, as the graphs they had drawn slid on top of the answers, clearly showing if they were right or not (all of them were by this point). This short recording gives an idea of the whole process. I made it after the lesson, so it looks like I am annotating, but in class it was students names that appeared. Of course, the benefit of randomly generated questions is that then I could create 3 more instantly and get 3 different students to have a go (this time choosing those who I knew had struggled last lesson, and had intentionally avoided in round 1). I only needed to do this twice, but I could keep going if I needed. Then with a quick change of settings we got these questions. After a few of those, we pushed into combined transformations with these questions, and I showed them the answer for the first one. I asked them to put their answers in the chat, and they all got it correct. We had to talk about the importance of the order of the transformations later, but that wasn't on my mind just yet. Then we moved on to look at this example together as a class (available in the lesson sheet for this topic). Which I colour coded as below Then I sent them off to try two Your Turn questions in pairs, suggesting they use the annotate function to communicate with each other as they worked through the problem. Finally, as the lesson came to a close, I wanted them to quickly check their answers, so I whipped up a desmos file to reveal the answers.

1 Comment

Put yourself in these situations: A colleague is talking at lunchtime in the staffroom about having trouble with a particular student. They do the bare minimum, but won't do any extra even though they could do really well in the subject if they just applied themselves a little bit. After a day visiting your parents, your partner is upset about something your father said. This is not the first time, they have had a tumultuous relationship at best. You just want them to get along. You are a middle/senior leader, and an area of concern/improvement in your area of responsibility has been identified from some data. What is your default reaction to situations like these? Mine has always been to go into problem solving mode. Certainly as a Mathemacian, that is what I do: solve problems. But recently I have noticed that I do this in all areas of my life, both professional and personal. If I get involved in a problem, then I am aiming to solve that problem. I took stock of this position a couple of times over the last few years. The first time I really thought about it was when I started training as an instructional coach following the Impact Cycle by Jim Knight. I was fortunate enough to go to the Instructional Coaching Institute in 2019 to be trained by Jim himself, and it was am incredible experience, not only to be surrounded by 99 other people who were coaches, but to listen to Jim himself. There was so much to take away from that week. But one thing that really hit me was that a coach is not there to solve the teacher's problem, but rather to understand the problem and help the teacher solve their own problem (though not in a facilitative way assuming the teacher knows what to do, but in a constructive conversation as partners). Since then I have been fortunate enough to have many coaching conversations and have worked for an extended period with several teachers as their instructional coach. I feel that in these conversations I am actually quite good at not trying to solve the problem. But it seems to be mostly limited to the structure of a coaching conversation. In reading Kicking the Solution Habit recently, I was suddenly confronted with a behaviour I exhibit most of the time. I try to find solutions. In the post, Matthew Evans basically has one big message: before trying to find a solution to a problem, make sure you understand what the problem is. And this is the sticking point for many people, in my experience. It is quicker and easier to make your own interpretations of the problem and solve those, than to actually spend the time investigating the true causes of the problem and addressing those. The quick fix is easy in the moment (even if it doesn't last), whereas actually solving the problem takes a lot of time and energy to explore what the true problem is. So, whilst I find myself able to do this in the confines of a coaching conversation, it is the structure of that conversation that acts as my cue to behave that way. When in another situation, be it an impromptu chat with a colleague or a conversation with my wife about our children, I fall back on my problem solving ways, trying to fix the problem instead of understanding it first. One area where this has been very evident is in my role as lead for teaching and learning. Early on in my time in this role, I wanted to enact quick solutions: an inset on this topic, a collaborative professional development day. But as I have gained experience, reflected and gotten better at the job, I have realised that if you want to implement anything, you have to take it slow, not just to get buy in (though that is important), but to make sure you are actually addressing the real problem, and not some surface detail that is really just a symptom. I want to improve at this. I want to be better at uncovering the real problem, and listening intently to people before trying to solve the problem. But I have a ways to go. I need to change a lifetime habit, and that is difficult. I need to work out some cues for myself to put me in the right frame of mind. I know I can do it, I just have to transfer what I do in a coaching conversation to other situations. But that is difficult. It isn't a quick fix. I am making headway. I have spent time identifying what the real problem is (I like to problem solve) where in the past I would have put the blame for failed fixes on the other person (they clearly didn't do it right). I am making progress. But I need to keep analysing the problem. Are you a problem solver? Are you always looking for a solution, rather than trying yo understand the problem?

|

Dan Rodriguez-Clark

I am a maths teacher looking to share good ideas for use in the classroom, with a current interest in integrating educational research into my practice. Categories

All

Archives

August 2021

|

|

Indices and Activities

|

Sister Sites

|

©2012-2023 Daniel Rodriguez-Clark

All rights reserved |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed