|

Put yourself in these situations: A colleague is talking at lunchtime in the staffroom about having trouble with a particular student. They do the bare minimum, but won't do any extra even though they could do really well in the subject if they just applied themselves a little bit. After a day visiting your parents, your partner is upset about something your father said. This is not the first time, they have had a tumultuous relationship at best. You just want them to get along. You are a middle/senior leader, and an area of concern/improvement in your area of responsibility has been identified from some data. What is your default reaction to situations like these? Mine has always been to go into problem solving mode. Certainly as a Mathemacian, that is what I do: solve problems. But recently I have noticed that I do this in all areas of my life, both professional and personal. If I get involved in a problem, then I am aiming to solve that problem. I took stock of this position a couple of times over the last few years. The first time I really thought about it was when I started training as an instructional coach following the Impact Cycle by Jim Knight. I was fortunate enough to go to the Instructional Coaching Institute in 2019 to be trained by Jim himself, and it was am incredible experience, not only to be surrounded by 99 other people who were coaches, but to listen to Jim himself. There was so much to take away from that week. But one thing that really hit me was that a coach is not there to solve the teacher's problem, but rather to understand the problem and help the teacher solve their own problem (though not in a facilitative way assuming the teacher knows what to do, but in a constructive conversation as partners). Since then I have been fortunate enough to have many coaching conversations and have worked for an extended period with several teachers as their instructional coach. I feel that in these conversations I am actually quite good at not trying to solve the problem. But it seems to be mostly limited to the structure of a coaching conversation. In reading Kicking the Solution Habit recently, I was suddenly confronted with a behaviour I exhibit most of the time. I try to find solutions. In the post, Matthew Evans basically has one big message: before trying to find a solution to a problem, make sure you understand what the problem is. And this is the sticking point for many people, in my experience. It is quicker and easier to make your own interpretations of the problem and solve those, than to actually spend the time investigating the true causes of the problem and addressing those. The quick fix is easy in the moment (even if it doesn't last), whereas actually solving the problem takes a lot of time and energy to explore what the true problem is. So, whilst I find myself able to do this in the confines of a coaching conversation, it is the structure of that conversation that acts as my cue to behave that way. When in another situation, be it an impromptu chat with a colleague or a conversation with my wife about our children, I fall back on my problem solving ways, trying to fix the problem instead of understanding it first. One area where this has been very evident is in my role as lead for teaching and learning. Early on in my time in this role, I wanted to enact quick solutions: an inset on this topic, a collaborative professional development day. But as I have gained experience, reflected and gotten better at the job, I have realised that if you want to implement anything, you have to take it slow, not just to get buy in (though that is important), but to make sure you are actually addressing the real problem, and not some surface detail that is really just a symptom. I want to improve at this. I want to be better at uncovering the real problem, and listening intently to people before trying to solve the problem. But I have a ways to go. I need to change a lifetime habit, and that is difficult. I need to work out some cues for myself to put me in the right frame of mind. I know I can do it, I just have to transfer what I do in a coaching conversation to other situations. But that is difficult. It isn't a quick fix. I am making headway. I have spent time identifying what the real problem is (I like to problem solve) where in the past I would have put the blame for failed fixes on the other person (they clearly didn't do it right). I am making progress. But I need to keep analysing the problem. Are you a problem solver? Are you always looking for a solution, rather than trying yo understand the problem?

0 Comments

I have just finished reading The Teaching Delusion by Bruce Robertson, and it hit all the right notes for me. I found myself nodding along, lapping up what Robertson says, constantly thinking "This is exactly what I think, but said so much more eloquently." In fact, I am thinking of copying a few extracts to give to people when I can't put into words my own thoughts! I jest, of course. There were plenty of insights in the book that I had not thought about before, and a couple of things I disagreed with. The main premise is that no matter how good teaching is, it can always be better. This has been a point I have made at the start of each new school year since getting the job of T&L Coordinator, and my most recent phrasing has been "It is both our right and our duty to continue to improve our teaching". I use this wording carefully, to instil the idea that it is our right to want to continue to improve ourselves, get better at our jobs, and become better teachers. This aligns with Robertson's idea of a Professional Learning Culture. On the other hand, we serve a community of children and their parents (who, in my case, pay a fair amount of money for our services), and it is also our duty to them to do the best job we can, which includes continually improving our teaching. Our duty to the parents who pay, yes, but mainly our duty to the young people we have the pleasure of working with, whose future depends so much on what we say and do, how we make them feel, and what they learn from us. Robertson asserts that The Teaching Delusion is made up of three factors:

I have been working on what I call the Aspects of Teaching, which is designed to underpin our Instructional Coaching Programme. The purpose behind this is to give coaches and teachers some broad areas of what we do to talk about, but also split it up a little bit to direct conversations to the most important parts that teachers want to work on. Below is the Aspects of Teaching. It should start automatically, and takes about a minute to play through the whole animation. There is a static image version here. Hopefully it is fairly self explanatory, which is why I have produced it in an animation form. But by splitting what we do into the 4 big Aspects, and then focusing on a particular detail within one of these, I am hoping to help create useful conversations. For each Aspect there will be a set of strategies taken from various sources, including

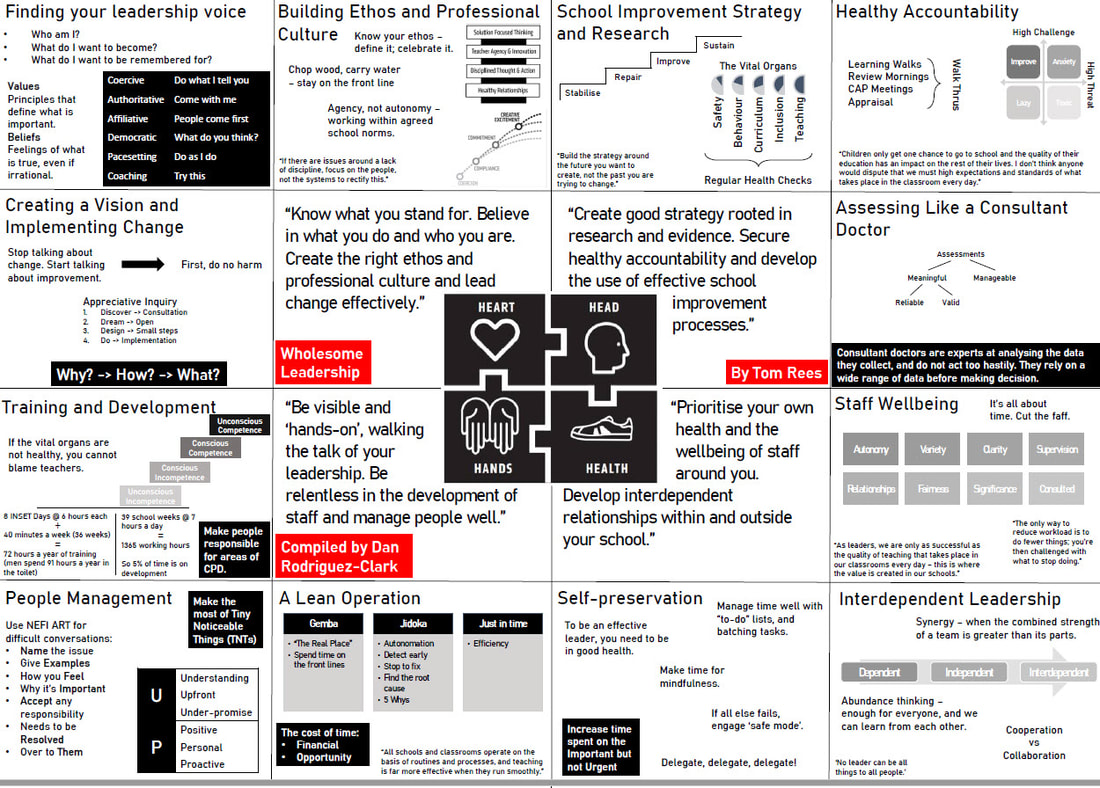

Wholesome Leadership by Tom Rees is a whole approach to school leadership. It is based around the model of the heart, the head, the hands and the health of school leaders, and goes into detail as to what successful leaders in schools do in each of these categories. Throughout the book, Rees tells personal stories of how he has developed as a leader in the different aspects, as well as giving specific examples of his experiences. This personal touch really helps the book feel more authentic, as you can tell it is written by somebody who has lived these experiences. This is balanced nicely by the interviews with others who are (or have been) involved in leadership in education, each giving their own perspective on one of the aspects of the Wholesome Leadership model. Before delving into the nitty gritty, Rees shares a handy planning tool, which he calls the Five Fives, for managing change, a big part of being a school leader. Throughout the book he refers back to this tool, providing a template at the end of each chapter to encourage leaders to engage in planning their changes. Also at the end of each chapter are a series of reflection questions for leaders to use to ascertain what areas they would like to work on in their leadership/school. Combining these with the Five Fives planning tool is an excellent way for leaders to take action after reading the chapter. Illustrated by Oliver Caviglioli, the visuals add to the whole experience of the book. Each chapter starts with a summary of key quotes which gives the reader a nice taster of what is to come. The highlight of the visuals are the WalkThrus for Learning Walks, Appraisal, CAP Meetings and Review Mornings. Each of the four parts of the Heart, Head, Hands and Health model is broken into 3 linked chapters. Although it is an easy book to read all the way through, it is also designed so you can jump to a particular chapter that you are interested in. I can see myself popping back to chapters on a regular basis to reacquaint myself with the ideas, now that I have read the whole thing. I have created a summary document of the book. The image is below, but you can find the PDF version here, which can be printed up to A2 (it also works pretty well in A3). Some more details on each chapter are below that.

|

Dan Rodriguez-Clark

I am a maths teacher looking to share good ideas for use in the classroom, with a current interest in integrating educational research into my practice. Categories

All

Archives

August 2021

|

|

Indices and Activities

|

Sister Sites

|

©2012-2023 Daniel Rodriguez-Clark

All rights reserved |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed